The Chinese economy has grown rapidly over recent decades to become the world’s second largest economy (based on market exchange rates).

China’s exceptionally high growth rate relative to the world’s large developed economies means that China has been the largest contributor to annual global economic growth for some time now.

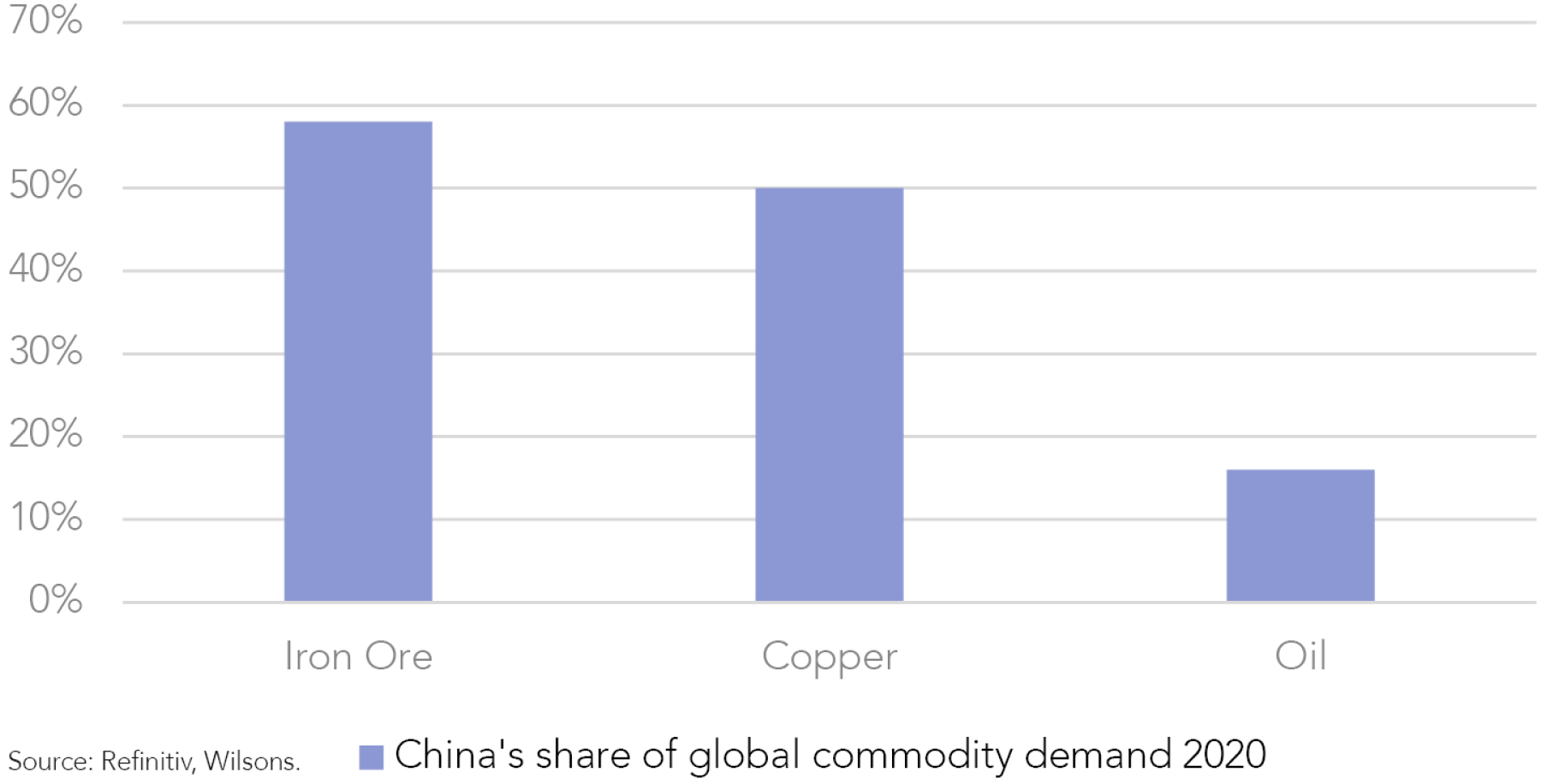

China is also a huge commodity consumer, with dominant demand shares in a large range of commodities. In particular, China accounts for close to 70% of seaborne iron ore demand (Australia’s largest export).

As a result, China’s rise over the last couple of decades has been of considerable benefit to Australia.

But while China‘s GDP growth has been impressive, it has been evident for some time that it is undergoing a gradual structural slowdown in its trend growth rate.

Largely as a result of the Covid pandemic, China’s growth has been unusually volatile. China also experienced a different growth pattern around the pandemic, contracting ahead of the rest of the world but rebounding earlier.

This growth rebound in 2020 and 2021 has been followed by growth slipping to very tepid levels this year, relative to historical standards. In the first quarter this year, China’s economy recorded its worst performance in over two years, contracting by 2.5% to be up only 0.4% year-on-year, well below its target of 5.5%.

The economy showed some modest improvement through the second quarter, though activity weakened again in July. Recent consensus estimates for the full year have growth improving over the second half to finish at around 3% for 2022. However, risks still appear skewed to the downside.

Zero-Covid, Zero Growth?

It appears 2 key factors have conspired to drag China’s 2022 growth rate well below its stated target of 5.5% - namely, the government’s zero-Covid tolerance policy and a significant slowdown in the property sector.

Covid-related weakness has been reflected in strict containment measures to slow the spread of the virus in several major cities this year, hurting consumer activity and disrupting supply chains.

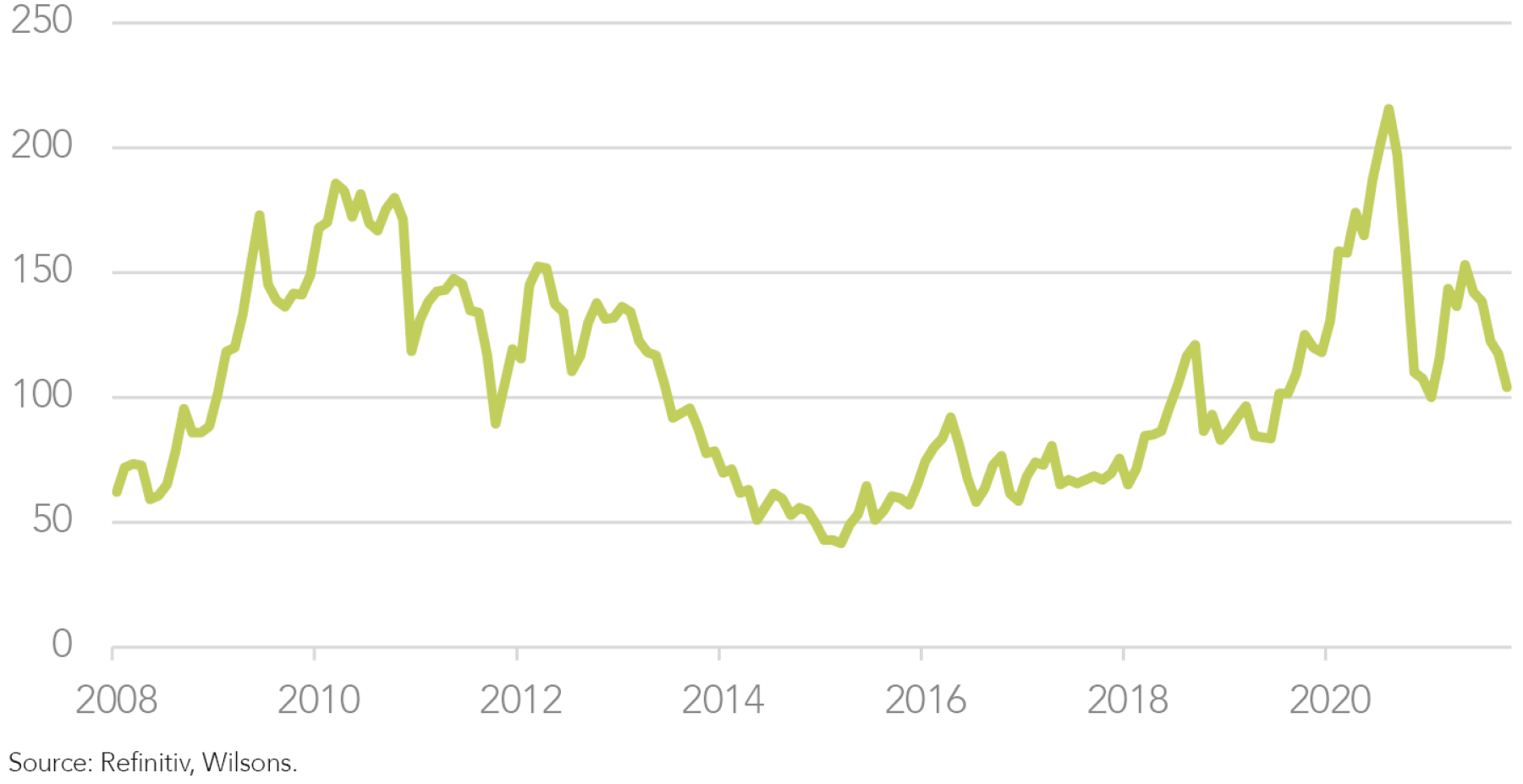

In addition, the real estate sector has been a significant drag on the Chinese economy for 12 months now. Real estate investment has declined by more than 20% from its peak 12 months ago.

Property activity has been constrained by restrictions on developer financing, which began in earnest around 12 months ago. The real estate slump has itself been compounded by restrictions on movement to deal with Covid outbreaks.

Various policy measures have recently provided some support. Mortgage rates and down-payment ratios on new property have been reduced. Additionally, government vouchers have been introduced to assist in the purchase of new property in a number of cities.

It has been well documented that China’s property slump has accentuated financial pressure on highly leveraged property developers (e.g., Evergrande).

The deterioration in funding conditions has led some developers to suspend construction and, consequently, some home buyers are withholding related mortgage payments (mortgage boycotts), which has affected a number of residential projects across China.

In this respect, the Chinese property market is somewhat unique in that 90% of housing units have been pre-sold. Overall, Chinese buyers have made very significant advance payments/prepayments (over and above deposits), often taking out mortgages to do so.

A number of commentators have warned of the risk that the largest source of developers’ financing – advance payments for pre-sold housing units – might very well dry up. This source has accounted for 50% of real estate developers’ total financing in recent years, with bank financing representing the residual.

We do not believe the current housing slump will morph into a financial crisis of the sort that occurred in the US in 2007/2008 before infecting the global economy. China has significantly more control over the current situation, and the impacts on the global economy are more related to the real economy than the financial economy. However, the scale of the property workout problem is significant.

Moreover, without an improvement in the housing market, a meaningful business cycle recovery in China is unlikely.

Historically, all recoveries in China’s broader economy since 2009 occurred alongside a revival in property sales. The importance of the property market goes beyond its size. Rising property prices lift household and business confidence, boosting aggregate spending and investment.

The risk is that a sluggish housing market and falling house prices continue to undermine consumer and business confidence. This, along with uncertainty related to the dynamic zero-Covid policy, will dent consumer spending and other forms of private investment spending.

No Big Bang Stimulus

As already discussed, China has been progressively supporting growth with policy easing this year. This stands in stark contrast to much of the rest of the world, where policy is getting incrementally more restrictive.

So far, China’s policy support is not proving to be the big bang stimulus of the past 10-15 years. Stop-start Covid lockdowns, combined with the property malaise, have largely muted the impact of stimulus measures.

We expect Chinese authorities will continue to add incremental policy support to the economy generally, and to the real estate sector specifically. In response to economic weakness, Chinese authorities have increased a wide range of fiscal support measures while gradually increasing monetary policy accommodation. Authorities have most recently approved a fund (~AU$40b) to support selected property developers to complete projects. Other measures have included consumption vouchers to support retail sales and a marked acceleration in the commissioning of public investment projects.

Where to from Here for China?

China is unlikely to abandon current Covid policies in a big bang fashion. However, we would expect it to show progressively more tolerance over the coming 6-12 months, as vaccination rates rise and supplies of antiviral drugs become more available. The conclusion of the National Party Conference in October may usher in some incrementally more tolerant attitudes towards Covid containment. So, our base case is that Covid policy becomes less of a drag over the coming year.

While this should be a positive for the growth outlook, property headwinds appear structural rather than cyclical.

As already discussed, China will do everything in its (considerable) power to avoid a property crisis, yet it will be extremely reluctant (even if it is possible) to engineer a fresh property boom. Hence, a moderate cyclical revival in property activity is our base case over the coming year.

In the longer term, the property sector’s ability to remain an engine of Chinese growth is highly doubtful. As such, we would expect a return to a 5-6% growth pace to be relatively short lived.

China is still likely to achieve growth rates well in excess of developed economies but a long-term convergence appears inevitable.

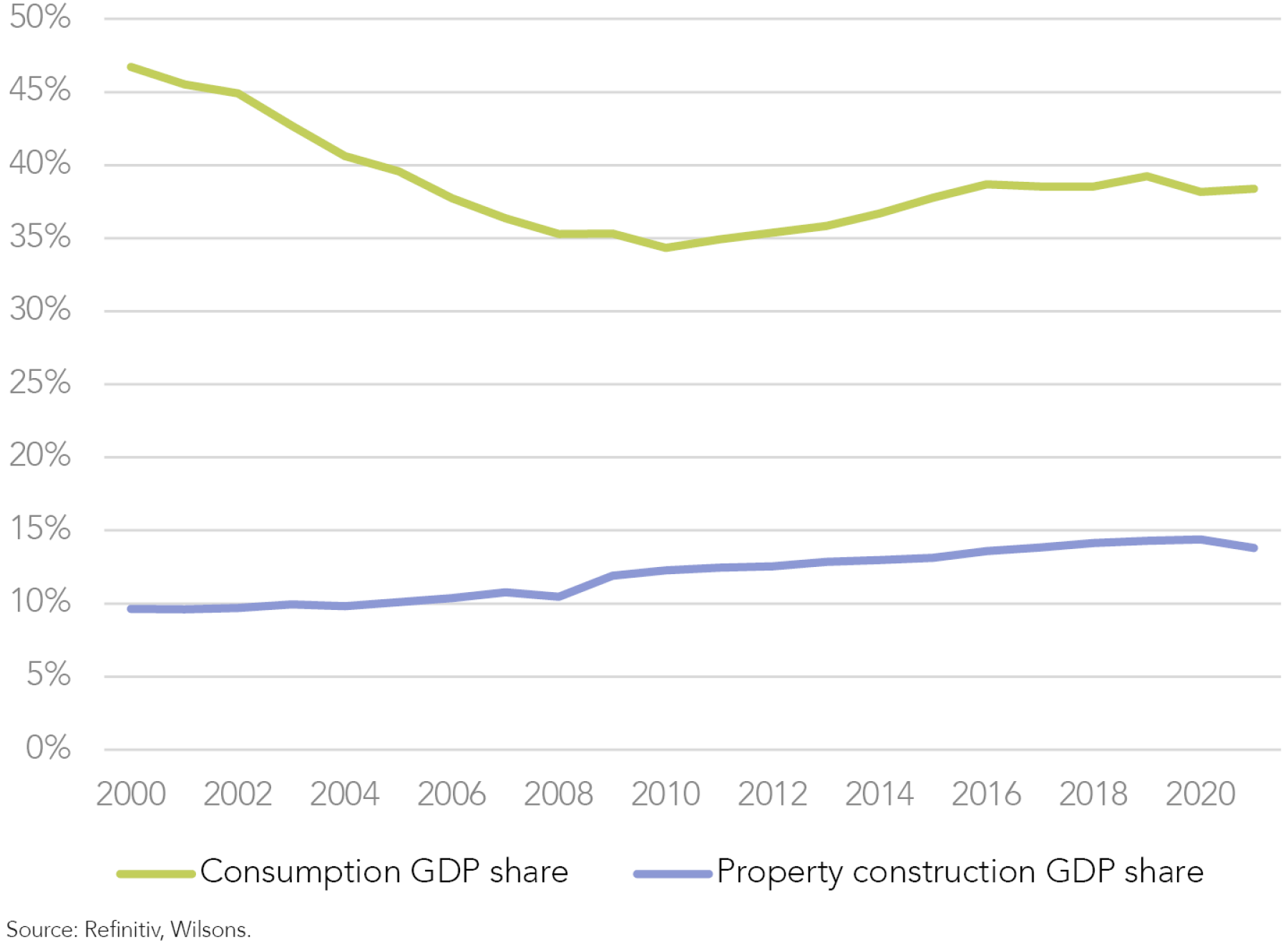

China faces a structural growth challenge posed by an imbalanced growth model premised on housing investment (likely over-investment), alongside heavy infrastructure investment. The contributions of infrastructure investments to growth continue to show more resilience than housing, but they too have their limits given their already substantial contribution to the economy.

The consumer currently represents a relatively small share of China’s GDP, sitting at around 40% (60% is typical for a developed economy). This share has scope to rise structurally given that GDP per capita remains low, that the savings ratio is high, and that productivity per worker is still on the low side.

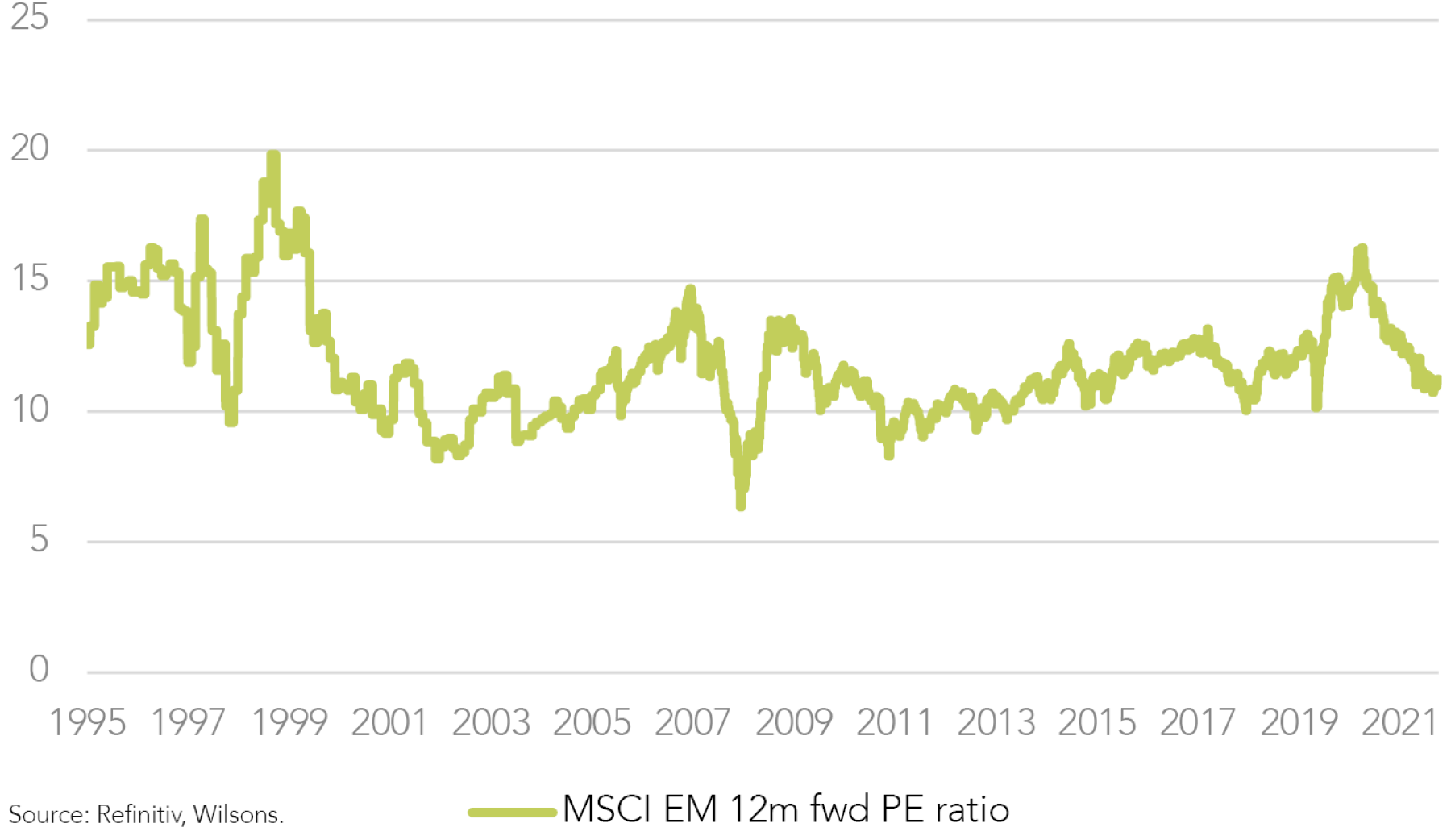

So, despite the additional challenge faced by a secular decline in its population, we believe the Chinese consumer still represents a huge opportunity. This supports a structural case for emerging markets exposure aided by the huge growth available in India, notwithstanding the current lackluster performance of the asset class.

From Australia’s perspective, the inevitable shift in China’s growth model away from housing investment and towards consumption has negative implications for our largest export, iron ore. While some cyclical revival appears plausible over the coming 12 months, we expect Chinese steel production has finally hit a structural peak. Combined with normalised supply conditions going forward, this means the medium-term risk to iron ore - which continues to sit well above the great majority of the cost curve - is well and truly to the downside.

Written by

David Cassidy, Head of Investment Strategy

David is one of Australia’s leading investment strategists.

About Wilsons Advisory: Wilsons Advisory is a financial advisory firm focused on delivering strategic and investment advice for people with ambition – whether they be a private investor, corporate, fund manager or global institution. Its client-first, whole of firm approach allows Wilsons Advisory to partner with clients for the long-term and provide the wide range of financial and advisory services they may require throughout their financial future. Wilsons Advisory is staff-owned and has offices across Australia.

Disclaimer: This communication has been prepared by Wilsons Advisory and Stockbroking Limited (ACN 010 529 665; AFSL 238375) and/or Wilsons Corporate Finance Limited (ACN 057 547 323; AFSL 238383) (collectively “Wilsons Advisory”). It is being supplied to you solely for your information and no action should be taken on the basis of or in reliance on this communication. To the extent that any information prepared by Wilsons Advisory contains a financial product advice, it is general advice only and has been prepared by Wilsons Advisory without reference to your objectives, financial situation or needs. You should consider the appropriateness of the advice in light of your own objectives, financial situation and needs before following or relying on the advice. You should also obtain a copy of, and consider, any relevant disclosure document before making any decision to acquire or dispose of a financial product. Wilsons Advisory's Financial Services Guide is available at wilsonsadvisory.com.au/disclosures.

All investments carry risk. Different investment strategies can carry different levels of risk, depending on the assets that make up that strategy. The value of investments and the level of returns will vary. Future returns may differ from past returns and past performance is not a reliable guide to future performance. On that basis, any advice should not be relied on to make any investment decisions without first consulting with your financial adviser. If you do not currently have an adviser, please contact us and we would be happy to connect you with a Wilsons Advisory representative.

To the extent that any specific documents or products are referred to, please also ensure that you obtain the relevant disclosure documents such as Product Disclosure Statement(s), Prospectus(es) and Investment Program(s) before considering any related investments.

Wilsons Advisory and their associates may have received and may continue to receive fees from any company or companies referred to in this communication (the “Companies”) in relation to corporate advisory, underwriting or other professional investment services. Please see relevant Wilsons Advisory disclosures at www.wilsonsadvisory.com.au/disclosures.